Unlike the buyer’s journey, it is the road less traveled.

A customer-deciding journey takes prospects down a path much more likely to end at a successful sale. It flips the well-worn notion of a buyer’s journey to instead focus on what the customer is doing rather than what you are doing to the customer. And it starts with a challenge to answer the fundamental question of, “Why should I change and why should I do anything differently?”

It is the first form of value that you must master as a seller. The primary sell strategy objective becomes: how to create a buying vision to drive momentum towards an eventual sale? It’s grounded in the notion of convincing a customer why they should make a change.

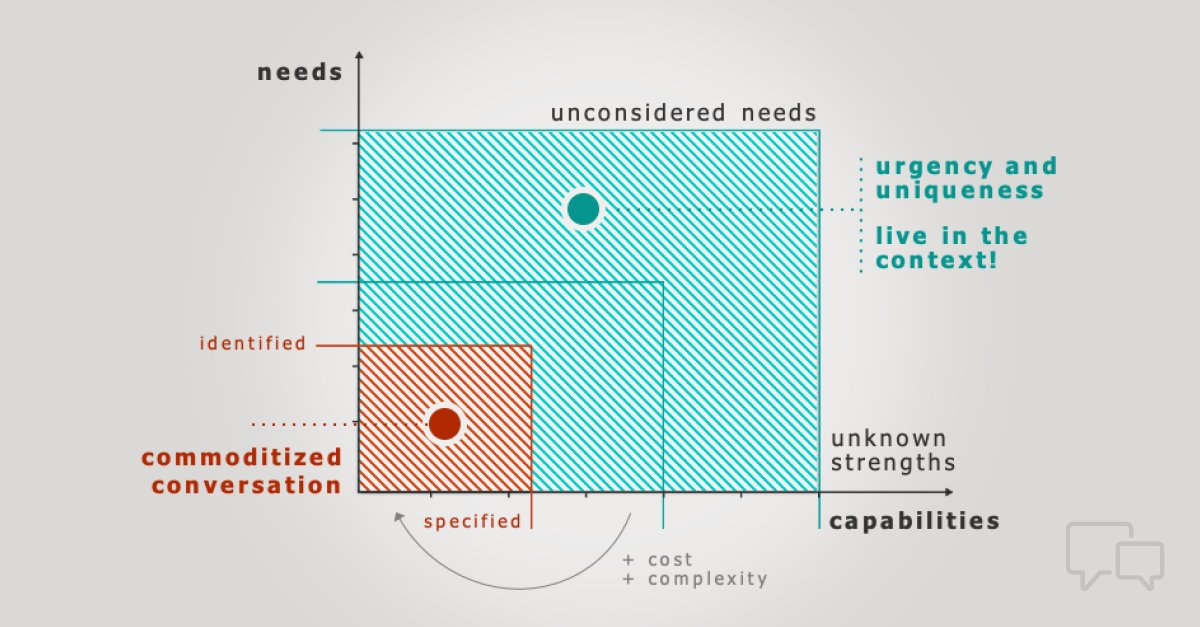

The customer’s Deciding Journey is also a matter of focusing on unconsidered needs. Instead of asking questions about the pains they know and recognize, the way to move customers to change is to show and explain the needs, problems, and missed opportunities of which they are unaware, according to Riesterer. These are problems they’re already living with, so there’s no real sense of urgency to change because they’ve figured out a workaround.

You need to open their eyes and reveal a need, a problem, a missed opportunity they don’t know they have. In psychology, persuasion is not possible without uncertainty. Exploring unconsidered needs introduces uncertainty about the way the customer does things today and the motivation to do something different.

Realization Through Stories With Contrast

Those who haven’t answered the question of “Why to Change?” are deniers, refusing to recognize they have a problem that’s big enough for them to change. To them, a case study that focuses on the end success of a solution is easily dismissed as a problem that isn’t big enough to take on the risk, the cost, or the perceived challenges of making a change to solve it. The breakthrough for many deniers is the story with contrast. People know this better as a before-and-after story.

There are before and after pictures of weight loss. Our brain needs to recognize that “I’m here and I want to get three.’ To actually cause them to say, ‘Yes, I need to change,’ you literally need that contrast. Your brain craves contrast in order to make a decision to change.

Once a prospect or customer has made this connection, they are ready to go along the journey with you to the proof point.

However, take it slow. Be mindful of rushing to the sales pitch too soon. There’s a strong temptation to race through the “before” effort to help prospects recognize they simply can’t stay where they are. While a story with contrast starts by discussing someone like them, it segues to posing questions like: How are you dealing with this in your organization? Does it seem as severe in your organization? It’s not a leap straight to a solution discussion.

Patience is key. You need to pause, let the “before” breathe, allow them to answer questions about the problem, and take ownership of it. Product-driven pitches and most case studies that focus primarily on results bypass the vital context that sets the selling stage. Results are positioned too soon.

You know, you can’t wait to get there. But the problem is that, while you may be ready to talk about a solution, your prospect or customer isn’t ready to go there yet.

You’ve got to let them marinate on it and answer their own questions after you’ve presented that ‘before’ scenario. Self-persuasion is the most effective form of persuasion. As good as you think you are, and you want to get to the part where you persuade them, let them persuade themselves.

Before-and-after stories are deliberate steps forward, and you pause after each move, asking questions, then engaging and allowing realization and affirmation to take root. An actual decision to purchase comes in two parts—emotional and intuitive. A prospect must believe they need to leave their status quo by identifying enough value for them to emotionally and intuitively disengage from their current approach.

The capacity for language and the reason to explain a decision actually lives in your rational/logical brain. So when we talk about elevating value, we’re literally talking about moving that value up into the rational and logical part of the brain that justifies and validates a decision. We like to convince ourselves and the people around us that we made rational rather than an emotional decisions.

Moving To The Capture Stage

Think of capture value as protecting your margin and/or justifying your pricing premium. In many sales cycles, capture value appears as the negotiation phase where a customer is likely asking the question, “Why should I pay what you’re asking?”

Customers typically believe they shouldn’t pay what a supplier or vendor asks for. It’s part of the buyer psychology of needing to feel you’re getting a great deal on the products or services you purchase. The traditional sales thinking suggests that the person who speaks first loses. By first suggesting a price, a seller may believe it puts them at a disadvantage because a buyer might have been willing to pay more had you allowed them to name a price.

The reality is they’re probably not willing to pay more than what you wanted to ask for. Inviting them to make an offer through a question such as, “How much are you looking to spend?” leads to a negotiation centered on driving that number up.

Anchoring and justification in a first offer are how to capture value:

- Anchoring: Put a number out there that’s a high target

- Justification: Then give them a slight discount

But give it to them for a reason. For example: because they’ve been a loyal customer or responded within a timeframe. Then the discount doesn’t feel arbitrary. There’s a reason they got it.

Driving a customer-offered price higher makes them feel that they lost the negotiation. A seller making the first offer and perhaps suggesting this is the product or service’s actual cost or service gives you a plan to concede—and give a buyer a perceived win.

You will drop that initial offer a little bit, but the customer will feel like they won.

Better than a customer takes you off your high number and target than try to claw back from the low number they gave you. It’s a matter of overcoming the psychological desire to win by recognizing that sometimes losing isn’t such a bad thing. In the case of price negotiations, it’s often a bigger win.

You don’t want your own psychology to be in play here. You want the customer to feel like they won. And I can guarantee that there’s a lot of margins that you’re leaving on the table if you follow the adage of the person who speaks first losing.